Review by Naomi Racz

Review by Naomi Racz

Coyotes have been making the news a lot lately, mainly because they have been eating cats and small dogs, and these pets’s owners are understandably not happy about it. Coyotes are making a home for themselves in the city and, as often happens when animals settle among humans, conflicts have arisen.

Chicago, despite being the third largest city in the US, has been no exception to this trend and Gavin Van Horn counts himself lucky to have encountered these urban coyotes. After all, coyotes have been venerated by Native peoples in the Americas for thousands of years. Van Horn believes that this ancient deity can also help lead us towards a modern day urban land ethic: an ethic for how we can better adapt our cities to meet the needs of human animals, non-human animals, and the wider ecological community.

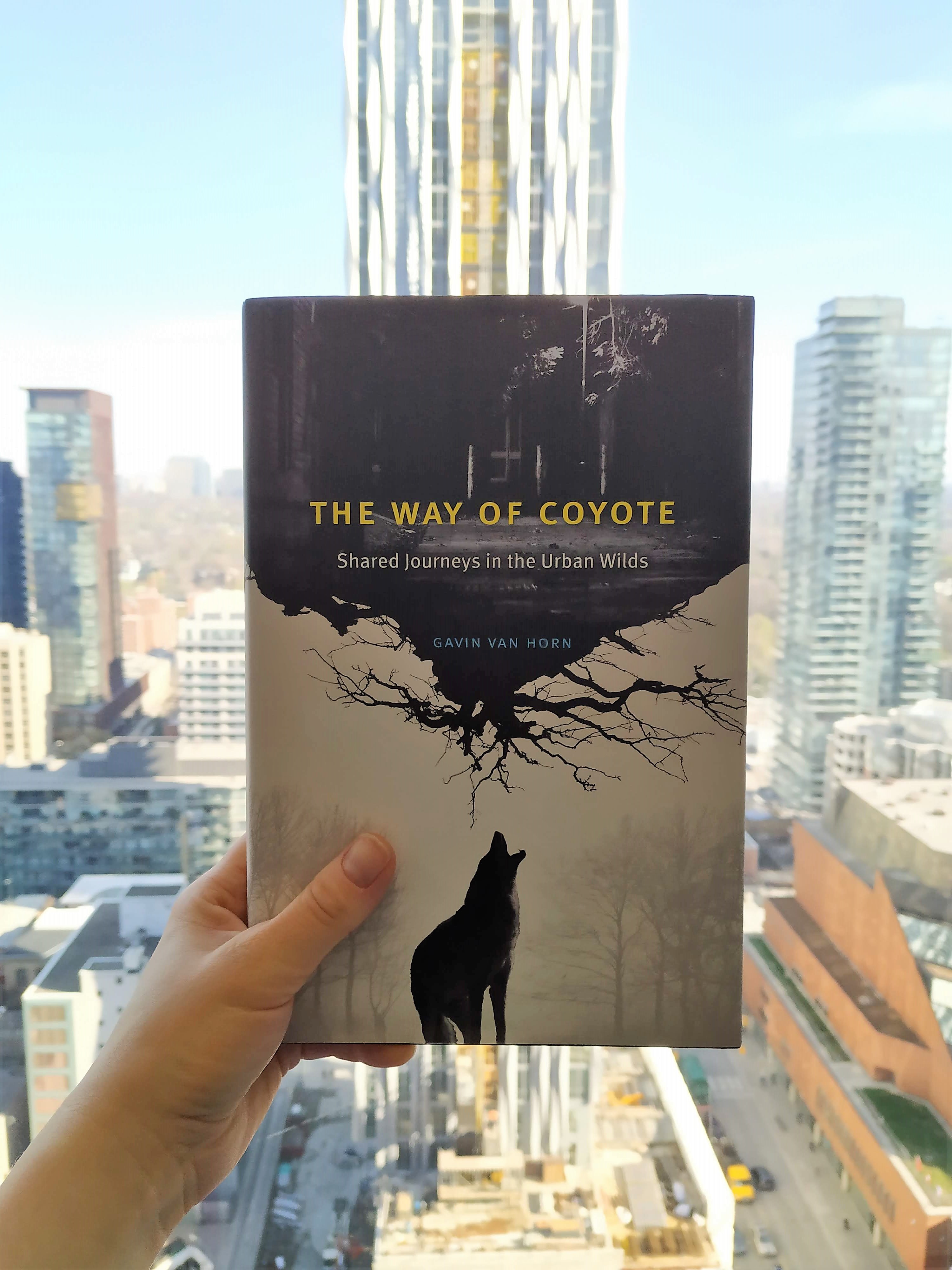

The Way of Coyote is Van Horn’s attempt at articulating an urban land ethic through stories. Van Horn explores many parts of the city, from a small pocket park to the shores of the vast Lake Michigan, and he encounters many different animals along the way: beavers, peregrines, black-crowned night herons, monarch butterflies, voles, bison, honeybees, and, of course, coyotes. To anyone who has ever questioned whether there is nature in the city, this book gives a firm nod. Each story is packed with reflections on human-animal relations in an urban context, revealing a mind that has not only spent many years living in the city, but has clearly spent a lot of time dwelling on it.

Van Horn also meets with many people working to understand, protect, and restore the urban environment. It was these people and their stories that I found most inspiring – stories of people trying to revitalize “throwaway landscapes”. People like Sherry Williams who is transforming the derelict Pullman factory, which once employed many African Americans who came to Chicago for the opportunities denied them in the South, into a bird oasis, where young people can learn about both bird migration and African American migration. Or people like John Ellis and Elvia Rodriguez-Ochoa who have a vision to transform an abandoned rail line in the neighbourhood of Englewood into an elevated trail, despite the odds stacked against them: the area’s declining population and loss of vitality, redlining, and toxic soil no one wants to deal with.

The Way of Coyote does not paint a rose-tinted picture of nature in the city. Van Horn fully acknowledges the dereliction, the poisoned waterways and land left toxic by industry, and the inequality – the north of Chicago got it’s elevated trail, the 606, long before Englewood. But neither is this a story of nature in perfect balance with the city. It’s a story of potential. Van Horn quotes one of my favourite passages from Gary Snyder’s essay “Good, Wild, Sacred”:

The best purpose of [wilderness] studies and hikes is to be able to come back to the lowlands and see all the land about us, agricultural, suburban, urban, as part of the same territory — never totally ruined, never completely unnatural.

Never totally ruined, never completely unnatural. There is potential here and many animals, including coyotes, are already taking advantage of it. As are the many people who are using the spaces available to them in the the city to encourage wildlife – people like Sherry Williams, or Lisa Hish, who is creating corridors for bees in the city, by planting flowers on street corners and other small patches of land.

One sentence in the book jumped out at me in particular and I scribbled it down: I celebrate the city and its possibilities. To me it sounds like a prayer for the urban wild lands, a mantra to be repeated as one wanders and explores the city, or simply encountering it during the day-to-day rhythms of life. It is the potential and possibility of the city as a life-giving place for humans and animals that Van Horn captures in his stories. That possibility is celebrated in this book, and celebration seems like a good place to begin.

The Way of Coyote: Shared Journeys in the Urban Wilds by Gavin Van Horn is published by the University of Chicago Press—our thanks to University of Chicago Press for providing a copy of the book in exchange for an honest review.